Teaching & Mentorship | Education | Q1 2019-2021

Designed and taught a 12-week university course on systems thinking for product and service design, mentoring 70+ students through research and prototyping.

Systems thinking is a way of investigating how things are interrelated and part of a whole, encompassing concepts, mindsets, tools, and methods for analyzing complex problems. As a designer, this approach is compelling to me because I'm sometimes confronted with unsolvable problems, where the best solution is about picking between tradeoffs. I remember that this was especially discouraging in design school when I wanted to propose solutions to complex social problems but what worked for one group was often at the expense of another. Systems thinking would have helped me better understand why it's so difficult to solve certain kinds of problems, and also pinpoint where and how I could make a practical difference. So when there was an opening for a sessional instructor at OCAD University to teach a third year undergraduate course on Systems Thinking, I took the opportunity to redevelop the course curriculum.

As a sessional instructor, I developed a course curriculum that introduced students to concepts and tools for applying a systems approach to complex problems. It was a 12 week course (3 hours each) with about 25 students. The first three classes focused on introducing key concepts of system thinking: components, relationships, and feedback loops (cause-and-effects). Then we moved on to communicating systems in visual ways through causal loop diagrams and stock and flow diagrams. Weeks 5-8 shifted from analysis mode to system interventions. Finally, the last few classes looked at how we can proactively identify possible downstream effects of our solutions. I iterated on the course for three years and prepared a fully virtual version during the covid pandemic, making adjustments to ensure that students who were remote and in different time zones could still participate.

I realized how complicated it is to actually change a system. It's easier said than done. Once complex systems are an everyday part of our lives, it would cause a lot of distress if we tried changing it, even if it was with a good intention.

Something I found interesting in this week's lessons was the mention that we cannot fully represent reality within a system diagram. We can try our best to break down and simplify the world around us, but there will always be areas of nuance that cannot be covered.

In starting to think about feedback loops I've gained a sudden awareness of just how many things are in dialogue with one another.

I almost forgot how fun it could be to quickly prototype with a group of people all giving each other ideas. I think this week was a good reminder not to get too invested in your first idea, and to spend time going through low fidelity exploration to find the right fit for a project.

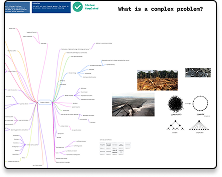

Activity: Brainstorm what is a complex problem by writing down words or images to describe a complex problem.

Facilitation method: Everyone in class contributed together to the same board (async students added on after) and shared afterwards.

Activity: Creating "Rich Pictures" to explore a problem situation related to each student's system of interest.

Facilitation method: Students worked individually on different boards and then shared out afterwards.

Activity: Learning more about system leverage points by trying to plot them on an iceberg model.

Facilitation method: Students worked in smaller breakouts of 2-4 so that they could have more intimate discussions. Space was provided with templates for async students.

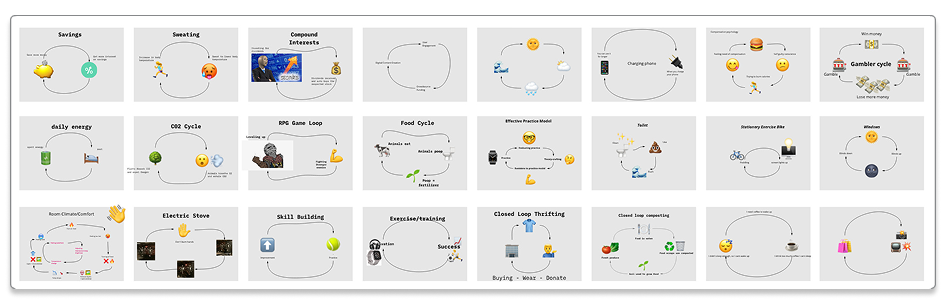

The course received positive feedback from students and other instructors because it gave them a concrete set of tools and vocabulary for talking about how things relate. There were a variety of different systems topics that students explored, from package delivery in condos to fake news, but they shared a common method for defining the system elements, interconnections, and purpose.

← All Projects

← All Projects